Golf Reset: Goodbye To The Almighty, Overprimped, Must-Be-Raked Daily Bunker?

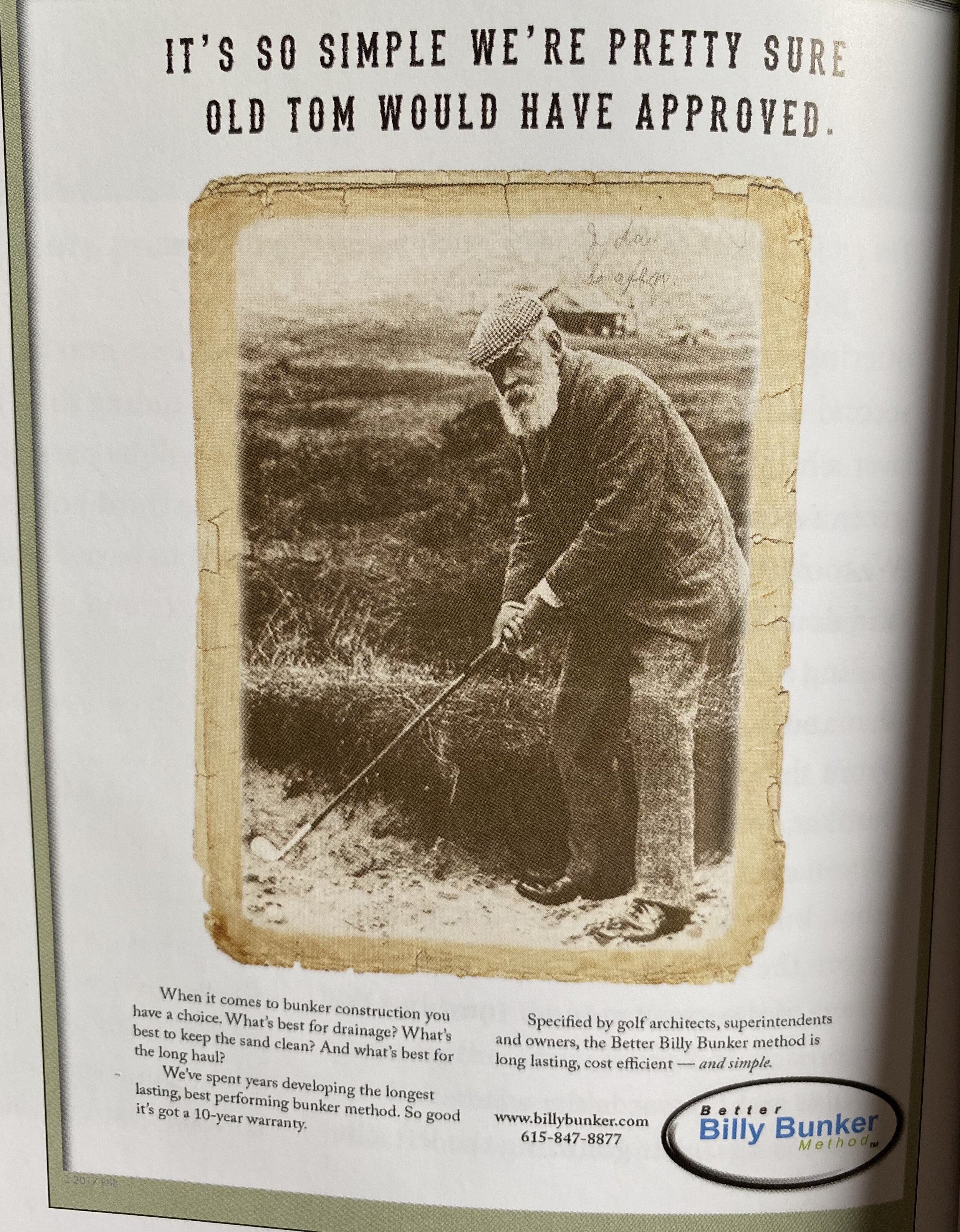

/Ad from Golf Architecture magazine suggesting Old Tom Morris would have approved of Better Billy Bunker.

I realize that jumping from the large scale topic of what really matters in golf—recreational vs. pro game—is a bit like jumping from talk of vaccines to multi-vitamins. Worse, doing so as we have as so much suffering is taking place in hospitals feels inconsiderate.

But the COVID-19 pandemic will accelerate trends in so many sectors, and as I noted in the introductory post to this occasional series, golf is not immune. So we march on with those caveats in mind and consider how this will change the bunker maintenance industry. And an industry, it has become.

Just a quick reminder here in case you skipped early Gaelic 101, “bunker” is derived from Old Scottish “bonker” and meant a chest or box, and became secondarily defined as a “small, deep sandpit in linksland”.

Since these bunkers appeared naturally on linksland, no one thought to arm them with a rake or liners to keep the shells out. That nonsense came later.

The first known reference in golf’s literature came in 1812, used in Regulations for the Game of Golf according to Peter Davies in the Dictionary of Golfing Terms.

Over the ensuing centuries golfers changed from accepting bunkers as accidental pits scraped out by divots or sheep, to demanding more maintenance. The shift was caused by two factors: the move from a match play mentality to a card-and-pencil, handicap-based game where tallying up a score could be disrupted by an unraked sand pit.

As golf courses moved inland, bunkers become very clearly man-made. The shift from natural to artificial changed expectations. Throw in the whining of golf professionals who were making their living on the links, and you have today’s irrational and expensive focus on perfect hazards. Even the Old Course rebuilds theirs every five years or so, which is why you get this kind of visual and psychological contrast from the old days to the present.

Hell Bunker on the Old Course a long time ago.

Hell at the 2015 Open Championship.

Besides the obvious changes in symmetry, artistry and beauty, the more “functional” Hell has been rigged with a flat floor to send balls closer to the face. Such artificiality goes against everything that makes the Old Course incredible. It could also be easily countered by raking the bunker once a week and letting whatever happens over those days leave the golfer wondering what they will find if unsuccessfully taking on Hell.

Not to pick on the Old Course, but the bunkers there used to look like this:

Despite the horrible looking lies to be found, golf somehow spread beyond the Old Course and became popular! All in spite of unfair bunkers that today would be seen as antithetical to growing the game.

Still, there were hopeful signs before the pandemic that the minimalist, scruffy, less-defined bunker was becoming more acceptable than the maintained bunker. The look of age, erosion and imperfection has become attractive again in part because of the thrill golfers find in overcoming such a bunker compared to carrying an overprimped hazard.

Here is a modern bunker, maintained for a tournament round, but otherwise looking ancient and imposing in an appetizing way:

Increasingly American superintendents have mimicked the Sandbelt concept of Claude Crockford’s day (and today) only raking bunker floors.

Here’s what a Kingston Heath bunker looked like in 2011:

With good intentions, this is an Americanized take on less raking. Though it’s mostly born out of a desire to prevent buried lies while ensuring clean, colorful, sanitary sand conditions:

In times of societal or economic trouble, bunkers have been filled in by courses. Even a master bunker creator like A.W. TIllinghast set out on his mid-1930s “PGA tour” of American courses looking for ways to save money. Bunkers topped his list.

However, filling these sandy things falls into the baby-with-the-bathwater class of overreactions. Especially these days where so much time and discussion is put into bunkers.

Which brings us to the rake.

Even though the chances of the coronavirus lingering on the surface of a rake seems extraordinarily slim, the removal of them from most golf courses allows us to think about a version of golf where hazard perfection is both antithetical to the role of a bunker and unnecessarily expensive.

The height of insanity might be seen as the time when courses spent bundles on various liners to keep sand in place and loose impediments out to prevent damaging nicks to clubs. Maybe having a chip or dent on the wedge will be scene as a bad of honor while bringing back genuine fear factor of landing in a bunker.

An entire cottage industry centered around selling bunker products reached a zenith when a golf architect, consultubg with a governmental agency to craft proposal specs, emphasized a costly bunker renovation using one particular liner product.

Turns out, the architect was president (at the time) of the bunker liner company that was recommended.

Concerns about making a course better and highlight its special heritage? Non-existent. Thankfully the scam was outed and he lost the design job. Now even the American Society of Golf Course Architects, of which he is a member, says the lifespan of an American bunker is twenty to twenty-five years, a big improvement from not long ago when ten years was the number.

Some of this bunker maintenance mania stems from the issues presented in the first golf reset post: making the professional golf bigger than the sport. But as easy as it seems to blame televised pro golf for many expensive trends, the bunker neuroses is mostly on average golfers fussing about their scorecard. Then again, there are you Scott Stallings’ of the world declaring unraked bunkers as a line-crossing that would make precious pros reconsider sending in their entry form to the first post-COVID-19 tournaments.

Think of bunkers and the all-mighty raking that was so cherished: imagine if footprints on beaches were deemed unsafe, and only the beaches raked and filtered daily were allowed to be open? The cost of such maintenance would be astronomical. Plus, the wait for beaches to be open after the maintenance teams had been through would drive everyone mad. A less extreme version of such nonsense occurs with golf course bunkers.

No one expects us to return to the days of yesteryear (above). Maintenance crews will still maintain bunkers and courses will leave rakes out, but golf without rakes (for the time being) should be seen as an opportunity to highlight the waste of resources and energy spilled to prevent the indignity of a bad lie in a place you’re not supposed be.